Moving Beyond the Limits of Compliance

Even perfect compliance programs will not guarantee zero injuries. A safety culture with individual ownership is also needed.

Leaders of potentially hazardous operations face a very real struggle. They have the legal obligation to comply with OSHA regulations and a moral responsibility to keep people safe. They struggle with the fact that while compliance is expected and within their control, experience tells them employee behavior plays the primary role in safe outcomes.

How a team member decides to act in a given situation is decidedly not within the leader’s control. Consequently, when safety results aren’t what well-intentioned leaders aspire to, they often double-down on what they can control: compliance. This is all in the hope compliance will eventually win out over what they cannot control: individual decision making.

The result is a frustrating cycle of doing the same thing and expecting different results. It is also wrong on both counts: Compliance has limits that no amount of training can overcome. And, while human behavior is imperfect, it can be managed.

Compliance

Every line in OSHA’s 29 CFR 1910 was written in blood. Knowing through painful experience what and what not to do is of tremendous value. And, because these regulations are clear and objective, it is easy to measure how we are doing against them whether we are managers or enforcement officers.

There’s an old (and true) saying: What gets measured gets done. Let us add a corollary: What is most easily measured is most often measured and is, by the transitive property, what’s most often done. The undeniable value of compliance combined with this self-reinforcing nature is a trap. This trap leads companies to focus almost solely on compliance and omit other worthwhile efforts. Let’s begin by detailing why “compliance only” efforts fail.

Compliance asks others to spend their efforts and resources for the benefit of someone else.

The late Nobel Prize winning economist, Milton Friedman, had a wonderful method for predicting outcomes of spending money based on whose it is, and on whom it is spent. There are four categories, but the first two are most instructive here. The first is to spend your money on yourself. In this case, you are likely very careful about how much you spend, and you are going to be certain to get exactly what you want. The second is to spend your money on someone else, like buying a birthday gift for a friend. In that case, you’re still careful about how much you spend, but not nearly as concerned about what the person gets.

Compliance efforts work out of Friedman’s Category II. We are asking people to spend their efforts for the results we want. If the quality of your employee compliance behavior matches that of the birthday gifts you’ve received over the years, you understand why. Prescribed compliance therefore works best with vast oversight, but management is present only 10% of the time an injury occurs. No member of management is present when 90% of incidents occur. This indicates a serious gap in compliance-based safety programs.

It is not and cannot be comprehensive.

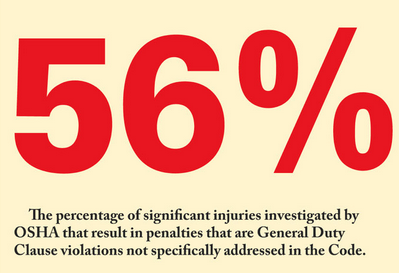

OSHA regulations are expansive, but it is impossible to write rules for every situation that might arise. The role good judgment plays in safety cannot be effectively replaced by more rules and procedures. Of all significant injuries investigated by OSHA that result in penalties, approximately 56% are General Duty Clause violations not specifically addressed in the Code. This is another gap a compliance program cannot effectively address.

It will not deter a bad actor, nor will it keep someone from “having a bad day.”

Almost everyone will say they agree to comply with safety rules, but not everyone intends to. If there is little chance of being caught, many people will act in a way most convenient to them. Ultimately, no one ever defies their own wishes—only those of others. Often these bad actors are identified by management, but the infractions may not seem significant enough to warrant corrective measures until it is too late. It is also true you don’t have to be a bad actor to have a bad day.

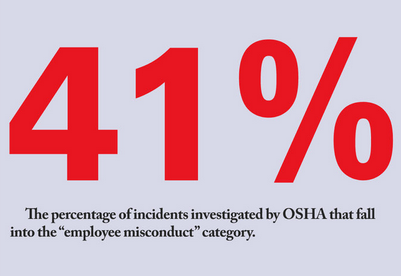

Even the safest team members act in ways they normally would not when struggling with personal issues. Approximately 41% of incidents investigated by OSHA fall into the “Employee Misconduct” category, and that is because compliance has little influence on them. Compliance-only systems let these people down.

The evidence is overwhelming. Every company has an obligation to follow the law, but even perfect compliance systems cannot guarantee zero injuries, including life-altering incidents and fatalities. Even so, excellent compliance may keep a company out of legal trouble (though that’s not guaranteed), but consider the ongoing costs: worker’s compensation, lost productivity, low morale, and damage to company reputation. These are real business costs organizational leaders are expected to minimize or eliminate. Then consider the human cost. Even if this is hard to quantify it is impossible to ignore. Every legitimate business exists because it in some way promotes the common good. When the net result of its actions is negative, employees, customers, vendors and ultimately society will turn against the organization. It is simply not enough to comply with the law.

The good news is there are effective, objective and measurable ways to fill the gaps left by compliance. It can be done by developing an ownership culture and introducing a moral element to safety. These concepts require further explanation.

Ownership

It is important for every employee to understand the company cannot guarantee their safety. While the company cannot be responsible for them, it is responsible to them.

The company is responsible to:

- Eliminate hazardous conditions.

- Provide proper training.

- Make available suitable personal protective equipment.

- Give accurate feedback and appropriate consequences for performance.

That said, only the employee can be responsible for their safe behavior, and this can be reasonably expected of any competent adult. Any thought that management can assume responsibility for another person’s safety is not only misguided but dangerous. It is unethical to mislead a team member, even with the best intentions, concerning an issue as important as safety.

If we intend employees to act like competent adults, it’s important we treat them as adults. We don’t allow children to enter many of our facilities, and rightfully so because they haven’t developed the good judgment to keep themselves safe. Good organizations are careful to hire competent adults, and leaders must be careful not to erode that asset by treating them otherwise. Holding people to high and reasonable expectations demonstrates respect. It fosters pride of association and pride of workmanship.

Most importantly, it sets up the employee for consistent safe outcomes.

Finally, if we want safety ownership, we must promote its benefits for the team member, not the company. When someone is injured there will always be negative impact to the company, but it will never be of the same magnitude as to the person injured or their family. When the focus is on rule breaking, incurred costs or lost productivity, the focus is on the least important part of the issue and by matter of course the organization will lose credibility. By focusing instead on the bigger issue, the human cost, not only does the organization gain moral authority but moves away from Friedman’s Category II and toward Category I, where people spend their efforts on themselves, not someone else.

The Moral Element

Safety must always have a moral element to it. Organizations hesitate to impose a moral choice on others, but if safety is viewed as simply a priority to be weighed against others, it will be. By positioning it as a higher-level responsibility safety will emerge as a clear and certain moral choice, because safety is a moral choice whether it is viewed as such or not. Positioning safety as a moral choice means following through with “always putting people first.” It is to step up and embrace our highest responsibility: It is unethical to put one’s self in harm’s way and equally unethical to knowingly allow a coworker to put themselves in harm’s way.

It is also immoral to trade someone’s safety for anything else, including efficiency, profit, personal comfort, or their approval. Efficiency and profit are well understood, but what do we mean by comfort or approval? This means it is not always easy to confront someone who is about to do something unsafe. We may be uncertain as to how the person will react. Or, we may have doubts as to whether we have a proper understanding of the situation. Any or all of these may give us pause or result in a failure to intercede. At such times everyone must understand they are making the decision to trade that person’s safety for their own comfort, and that is always an immoral transaction. The same holds true if we trade their safety to maintain their favorable opinion of us. Placing a coworker’s safety at risk to keep their approval is yet another immoral transaction.

People want to be the hero of the stories they tell themselves. If you ask someone if they would protect another from a dangerous situation, they will almost always respond affirmatively. Use that to mutual advantage and hold people to their highest opinion of themselves. This will require them to either behave consistent with that opinion or force them to construct a new self-image. It’s costly and more difficult to change their self-view. Most team members will not and cannot accept becoming the “moral coward” in their life story.

All conscientious leaders target zero injuries at their facilities, but few believe it realistic because they intuitively understand the limitations of most compliance-based safety programs. Hopefully, compelling arguments have been presented for ownership and moral choice being vehicles to move beyond those limitations and toward a reality where zero injuries is not only possible, but expected. But the greater challenge is turning these concepts into tangible results on the shop floor; in developing and promoting ownership in the workforce and effecting and gauging progress.

This article is Part I of a series. Part II will explore practical examples of how to develop and manage safety ownership and overcome the barriers commonly encountered.

Click here to see this story as it appears in the April 2019 issue of Modern Casting